OpenCV in Embedded Vision Systems in 2026: ARM, FPGA, and Scalable Architectures

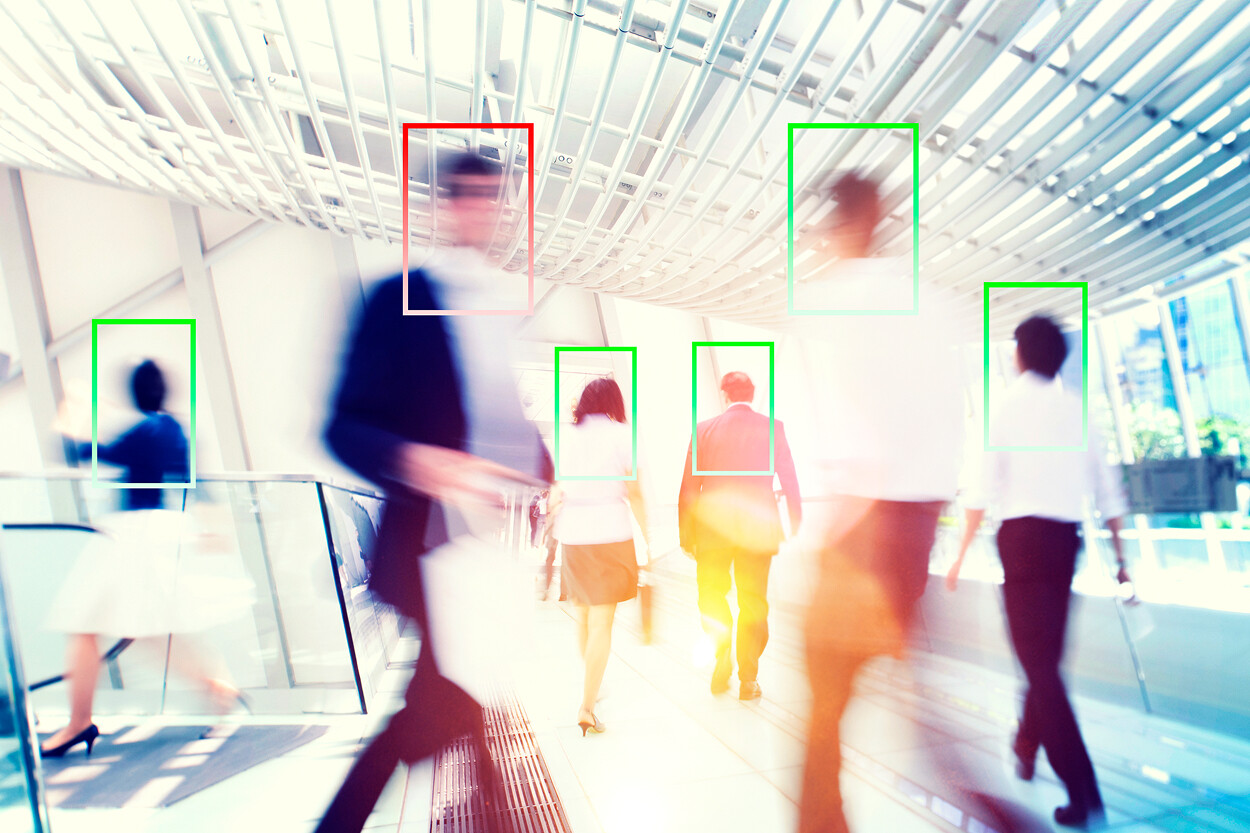

Embedded computer vision has changed noticeably since the early 2020s. In 2026, vision is no longer treated as an isolated feature or a software-only problem. It is a system-level capability that must operate under strict constraints on latency, power, thermal behavior, data privacy, and long-term maintainability.

OpenCV is still widely used in embedded vision projects, but its role has evolved. Treating OpenCV as a universal processing engine no longer reflects how production systems are built. In modern embedded platforms, OpenCV works best as part of a heterogeneous pipeline that combines ARM CPUs, hardware accelerators, and, in some cases, FPGA-based data paths.

This article explains how OpenCV fits into embedded vision architectures in 2026, when CPU-based processing is no longer enough, and how scalable systems are structured to survive real production constraints.

How OpenCV fits into embedded vision architectures in 2026

In 2026, OpenCV fits into embedded vision systems primarily as an orchestration and processing layer rather than as the core execution engine. It is commonly responsible for image acquisition, format conversion, classical pre-processing, geometric transformations, and coordination between different parts of the pipeline.

What OpenCV no longer does well at scale is carrying the full performance burden of the system. High-resolution streams, multi-camera setups, and real-time requirements quickly exceed what CPU-bound processing can handle within realistic power and thermal limits.

As a result, OpenCV typically sits between hardware blocks. It prepares data for accelerators, consumes their outputs, implements fallback logic, and glues together components that are executed elsewhere. This position makes OpenCV valuable, but only when its boundaries are clearly defined.

While OpenCV’s role has shifted toward orchestration rather than raw execution, this does not reduce its importance—it changes how teams must work with it day to day. Making OpenCV effective on ARM SoCs and FPGA-based platforms now depends on disciplined build configuration, selective module usage, hardware-aware optimization, and clear separation between CPU logic and accelerated paths, rather than treating the library as a drop-in solution. In production systems, the difference between a scalable vision pipeline and an unstable one often comes down to these practical choices, made early and validated against real hardware constraints.

Embedded vision constraints that drive architectural decisions

Several constraints consistently shape embedded vision systems in 2026.

Power and thermal limits are often fixed by industrial design. Many devices operate fanless or in sealed enclosures, where sustained CPU load is unacceptable. Latency requirements are increasingly deterministic rather than best-effort. In robotics, inspection, and safety-related systems, predictable timing matters more than average frame rate.

Data handling has also shifted. Instead of transmitting raw video, systems extract metadata and events at the edge. This reduces bandwidth, improves reliability, and supports privacy-first designs. These requirements fundamentally change how vision pipelines are structured and where computation is placed.

Within this context, OpenCV must coexist with hardware acceleration rather than compete with it.

OpenCV on ARM SoCs with heterogeneous acceleration

ARM-based SoCs remain the dominant platform for embedded vision in 2026. Most modern devices integrate ARM CPUs with GPUs, NPUs, or DSPs, each optimized for different workloads.

OpenCV can be used effectively on these platforms when its role is limited to tasks that benefit from flexibility and control flow. Typical examples include camera integration, buffer management, color space conversion, resizing, and classical filtering. These operations are predictable and integrate well with the rest of the system.

Neural inference, however, is usually not executed inside OpenCV. Even though OpenCV provides a DNN module, production systems increasingly rely on dedicated inference runtimes that map directly to NPUs. In this setup, OpenCV prepares input tensors, triggers inference through an external runtime, and post-processes results.

This separation allows systems to scale without overloading the CPU and avoids the performance cliffs that appear when OpenCV is used beyond its natural limits.

When FPGA acceleration should replace CPU-based OpenCV processing

FPGA acceleration becomes the right choice when systems require deterministic latency, high throughput, and predictable behavior under load. These conditions are common in industrial inspection, transportation, and safety-critical applications.

CPU-based OpenCV processing struggles in these scenarios because execution time varies with system load, cache behavior, and scheduling. Even well-optimized code can exhibit jitter that is unacceptable for real-time guarantees.

FPGAs address this by implementing fixed dataflow pipelines that process streams with bounded latency. Tasks such as filtering, normalization, edge detection, or feature extraction are often moved into FPGA fabric, where they execute in parallel and with predictable timing.

In these architectures, OpenCV does not disappear. Instead, it operates on data that has already been pre-processed by the FPGA. This reduces CPU load and allows OpenCV to focus on control logic, decision-making, and integration rather than raw pixel processing.

The limits of OpenCV in real-time embedded vision systems

OpenCV reaches its limits when systems demand strict real-time guarantees, high frame rates at high resolutions, or aggressive power budgets. These limits are not flaws in OpenCV itself but consequences of its general-purpose design.

When OpenCV is used as the primary execution engine under these conditions, systems often encounter late-stage performance issues. Latency becomes inconsistent, power consumption increases, and scaling to additional cameras or higher resolutions becomes impractical.

Recognizing these limits early is critical. OpenCV should not be stretched to cover workloads better handled by accelerators. When it is, system complexity increases without delivering reliable performance.

How scalable embedded vision pipelines are structured

Scalable embedded vision pipelines in 2026 follow a modular, heterogeneous structure. Responsibilities are clearly divided across components rather than concentrated in a single software layer.

Sensor input and early pre-processing are often handled as close to the hardware as possible, using ISP blocks or FPGA logic. Inference is executed on dedicated accelerators optimized for neural workloads. OpenCV coordinates these components, performs non-critical processing, and implements fallback paths.

This structure supports long-term scalability because individual blocks can be optimized or replaced without redesigning the entire system. It also simplifies validation and maintenance, which are increasingly important for products with long lifecycles.

OpenCV alternatives and complementary technologies

OpenCV rarely exists alone in modern embedded systems. It is commonly combined with vision graph standards, inference runtimes, and media frameworks that handle specific parts of the pipeline more efficiently.

These tools do not replace OpenCV entirely. Instead, they reduce the pressure on it by taking over performance-critical or highly specialized tasks. OpenCV remains valuable as a unifying layer that connects components written for different execution environments.

Conclusion

In 2026, OpenCV remains relevant in embedded vision, but only when used in the right role. It is no longer a complete solution for real-time vision on its own, nor should it be treated as one.

Effective embedded vision systems combine OpenCV with ARM-based SoCs, hardware accelerators, and FPGA pipelines to meet real-world constraints. OpenCV provides flexibility, portability, and integration, while specialized hardware delivers performance and determinism.

The key to success is architectural clarity. When OpenCV is placed where it fits best, embedded vision systems become scalable, reliable, and ready for production.

AI Overview

OpenCV remains a relevant component of embedded vision systems in 2026 when used as part of hybrid ARM and FPGA architectures rather than as a standalone processing engine.

Key Applications: embedded vision orchestration, ARM-based image processing, FPGA-assisted pre-processing, scalable vision pipelines.

Benefits: architectural flexibility, maintainability, clear separation of responsibilities.

Challenges: real-time constraints, power limits, integration with accelerators.

Outlook: OpenCV continues to serve as a coordination layer while performance-critical workloads move to specialized hardware.

Related Terms: OpenCV, embedded vision, ARM SoC, FPGA, hardware acceleration, vision pipeline architecture.

Our Case Studies

FAQ

How does OpenCV fit into embedded vision architectures in 2026?

When should FPGA acceleration replace CPU-based OpenCV processing?

Can OpenCV be used effectively with ARM SoCs that include NPUs?

What are the limits of OpenCV in real-time embedded vision systems?

How should embedded vision pipelines be structured for long-term scalability?