Battery Digital Twins for EVs

Why battery digital twins suddenly matter in production programs

A few years ago, “digital twin” in the EV battery world mostly meant a modeling slide in an R&D deck. Today, it shows up in real programs with real deadlines: fast-charging control, warranty risk forecasting, manufacturing quality, fleet operations, and traceability. The reason is simple. Battery packs are the most valuable and most uncertain subsystem in the vehicle. They are expensive, safety-critical, and their real-world degradation depends on usage patterns that are hard to predict from lab tests alone.

Operating conditions are also getting tougher. Charging rates are rising, thermal margins are being pushed for performance and packaging, chemistries are diversifying, and software-defined vehicles make “updateable behavior” the norm. In this environment, a battery model that is only accurate on a test bench is not enough. Teams want a living representation of each pack (or pack type) that stays aligned with reality as the vehicle ages, learns from telemetry, and can forecast outcomes rather than only report measurements. That is what a battery digital twin is in practice.

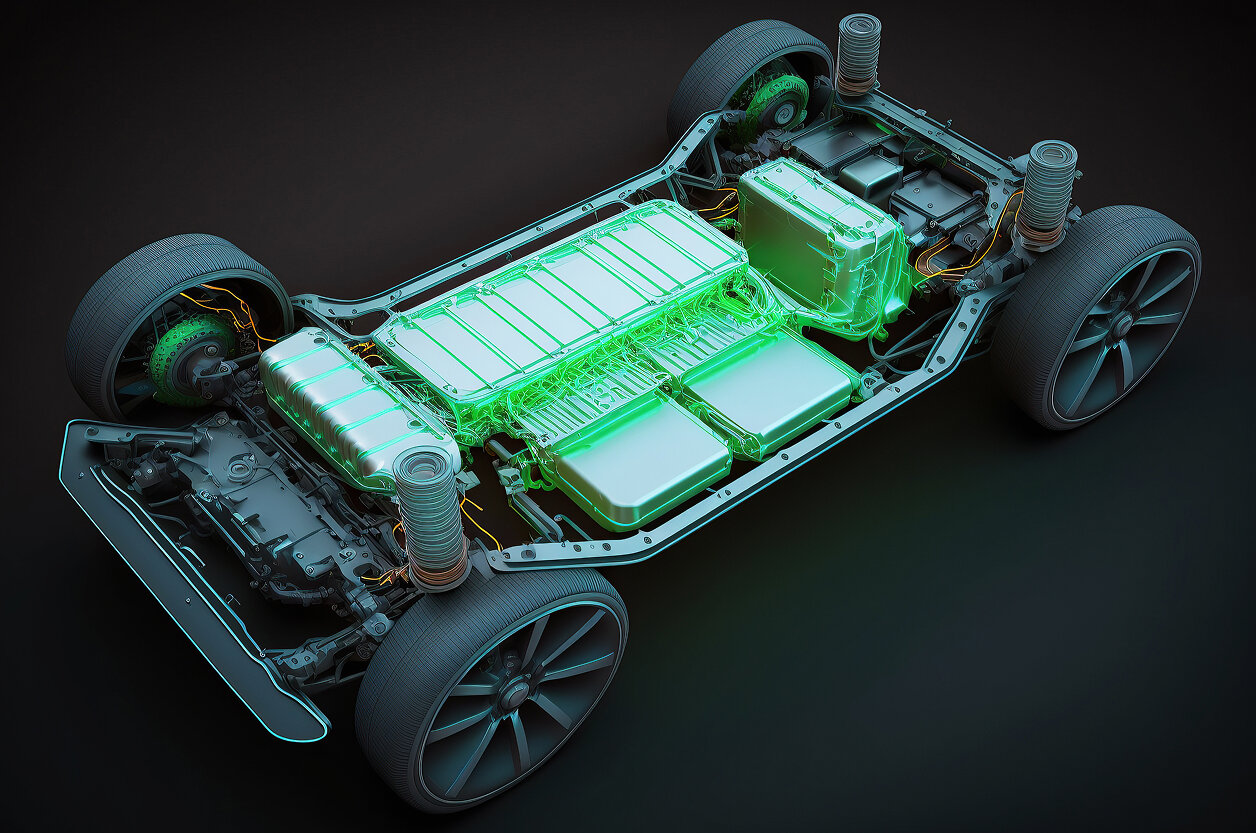

What a battery digital twin is, in engineering terms

A useful battery digital twin is not one model. It is a system that combines modeling, synchronization, and decision support.

At its core, the twin represents internal battery states you cannot measure directly, such as effective capacity, internal resistance growth, thermal gradients, and degradation indicators. It then uses real operational data to keep those estimates grounded in reality.

A practical twin usually includes:

- A battery behavior model (electrical plus thermal, with an ageing component)

- A synchronization loop that updates the twin from live telemetry

- A decision layer that turns estimates into actions (charging limits, power limits, service flags)

If you only build the first part, you have a simulation. The “twin” begins when the model is continuously anchored to what the pack is actually doing.

Two kinds of twins that often get mixed up

Battery digital twins are used in two different places, and mixing them up is a common reason projects stall.

The first is a manufacturing and product twin. It is about how the battery was built: cell lots, formation results, end-of-line test data, and quality fingerprints. It helps answer “why did this pack diverge from the average?”

The second is an operational twin. It lives with the vehicle in the field and focuses on usage: SoC and SoH estimation, degradation trajectory, anomaly detection, and remaining useful life.

The real value appears when you connect both. Packs do not start life identical. Small differences at birth can become big differences after thousands of cycles. A twin that knows the pack’s origin can be less conservative and more accurate.

What the twin buys you beyond a classic BMS

A classic BMS must be robust with limited observability and compute. It estimates SoC, monitors temperatures, enforces safety limits, and often uses semi-empirical approaches for SoH and power capability. That works well for baseline safety, but it becomes limiting when you push the system harder, especially during fast charging, extreme temperatures, and high-duty fleet usage.

A digital twin helps because it can estimate hidden states and predict outcomes. That shifts the system from “react and protect” to “predict and adapt.”

Two areas where this matters most:

- Fast charging control, where internal conditions and ageing strongly affect safe charge power

- Warranty and fleet planning, where you need forward-looking SoH and degradation trajectories, not just a snapshot

The key design choice: physics, data, or hybrid

Most teams do not fail because they pick the wrong algorithm. They fail because they pick a complexity level they cannot maintain.

Physics-first approaches use electrical and thermal models with parameter identification. They can generalize better outside the exact training data, but they require careful calibration and can be heavy if you do not reduce them correctly.

Data-first approaches learn mappings from telemetry to SoH, RUL, or internal parameters. They can be extremely effective when you have strong fleet datasets, but they are vulnerable to extrapolation errors when conditions shift.

Hybrid approaches combine both. They use a model structure that respects physical constraints, while learning corrections or parameters from data. In production EV programs, hybrids are often the most realistic path because they balance robustness and adaptability.

What data you actually need to start

You do not need a perfect dataset to start. But you do need reliable fundamentals and a plan to handle missing or biased sensors.

Minimum telemetry that most twins depend on:

- current, voltage, and multiple temperature points

- time history of charge and discharge events

- charging power and charging session metadata

What makes a twin significantly more valuable is context and identity: ambient temperature, duty cycle intensity, and a clean pack identity that links manufacturing history to field telemetry.

Where battery digital twins deliver the most value across the lifecycle

In design and validation, twins help reduce physical iterations and explore edge cases more systematically. The biggest benefit is not replacing testing, but focusing testing where it matters and understanding sensitivity to variation.

In manufacturing, a twin supports traceability and quality analytics. When you can connect process fingerprints to later field behavior, you stop treating warranty issues as “random variance” and start treating them as a preventable system property.

In operations, the twin is most valuable when it improves decisions that customers feel: fast charging consistency, better range confidence, fewer unexpected power derates, and earlier detection of abnormal behavior.

In second life and recycling, twin-based health evidence helps you value used packs with less guesswork. If you can show credible SoH, resistance growth, and a history of thermal stress, you can sort packs into reuse candidates more confidently and reduce expensive retesting.

A realistic architecture teams can build

A workable deployment usually splits responsibilities.

On-board, the BMS and pack controller enforce safety, handle real-time limits, and run estimation functions that must remain robust even when connectivity is absent.

Off-board, a backend twin layer aggregates fleet telemetry, runs heavier forecasting and population analytics, and generates insights that are not time-critical. This layer can recommend parameter updates, service actions, or charging strategy adjustments, but safety limits should still be enforced on-board.

The hardest part is the data thread. If you cannot consistently link pack identity, manufacturing history, service actions, and field telemetry, the twin loses context. Without context, you either become overly conservative or you become unreliable.

How to implement without turning it into a science project

The fastest path is to treat the twin as a product that evolves in stages.

Start with a twin for a pack type, not for every individual pack. Prove that it matches reality across temperature and load ranges. Then add synchronization and drift detection so the twin stays aligned in the field. Only after that should you let the twin influence operational decisions like charging profiles or power limits.

Two common “keep it real” rules help teams avoid overbuilding:

- If a feature cannot be validated with available telemetry and ground truth, it should stay advisory, not control-critical.

- If a model update cannot be rolled out safely and monitored for drift, it is not ready for fleet scale.

The problems teams underestimate

Sensor bias is the first. A twin is only as good as its measurements. If current or temperature readings drift, the twin will confidently infer the wrong internal state.

Ground truth scarcity is the second. You cannot capacity-test every pack regularly. That means you need validation strategies that combine sample-based testing, consistency checks, and drift monitoring.

Model drift is the third. Chemistries change, suppliers change, firmware changes. A twin must have versioning, re-calibration triggers, and governance around updates.

The fourth is organizational, not technical: data boundaries between suppliers, manufacturing, and aftersales often make it hard to build the end-to-end thread that the twin needs.

Where this is heading

The near-term direction is tighter integration between lifecycle data and operational decisions. More twins will become uncertainty-aware, because fleet decisions are risk decisions. More systems will use hybrid modeling because pure data-driven approaches struggle when conditions shift. And more programs will treat the battery as a managed asset: software and data continuously improve how it is charged, used, and maintained, while safety constraints remain strict.

AI Overview

Battery digital twins are synchronized, predictive models that connect manufacturing history and vehicle telemetry to improve SoH estimation, charging control, quality traceability, and lifecycle decisions for EV batteries.

Key Applications: age-aware fast charging and power limiting; SoH and RUL forecasting for fleets; anomaly detection and early fault warning; manufacturing traceability and quality analytics; second life grading and recycling planning.

Benefits: more accurate SoC and SoH in real conditions; safer, more consistent charging through adaptive limits; lower warranty uncertainty through better degradation prediction; earlier detection of abnormal behavior; better valuation of used packs with evidence-based metrics.

Challenges: sensor bias and data quality; scarce SoH ground truth; model drift across chemistry and supplier changes; weak data linkage between manufacturing and field; governance when twin outputs influence decisions; scalable lifecycle management for model updates.

Outlook: wider adoption of hybrid models and uncertainty-aware estimation; stronger digital thread linking production and operations; twins evolving into managed battery lifecycle toolchains that improve over time without compromising safety.

Related Terms: battery management system; equivalent circuit model; thermal modeling; state of health; remaining useful life; anomaly detection; digital thread.

Our Case Studies

FAQ

Do you need a digital twin for every cell in the pack?

Is a battery digital twin the same as a battery passport?

Can a twin improve fast charging without reducing safety?

Where should the twin run, in the vehicle or in the cloud?

How do you validate SoH predictions without frequent capacity tests?